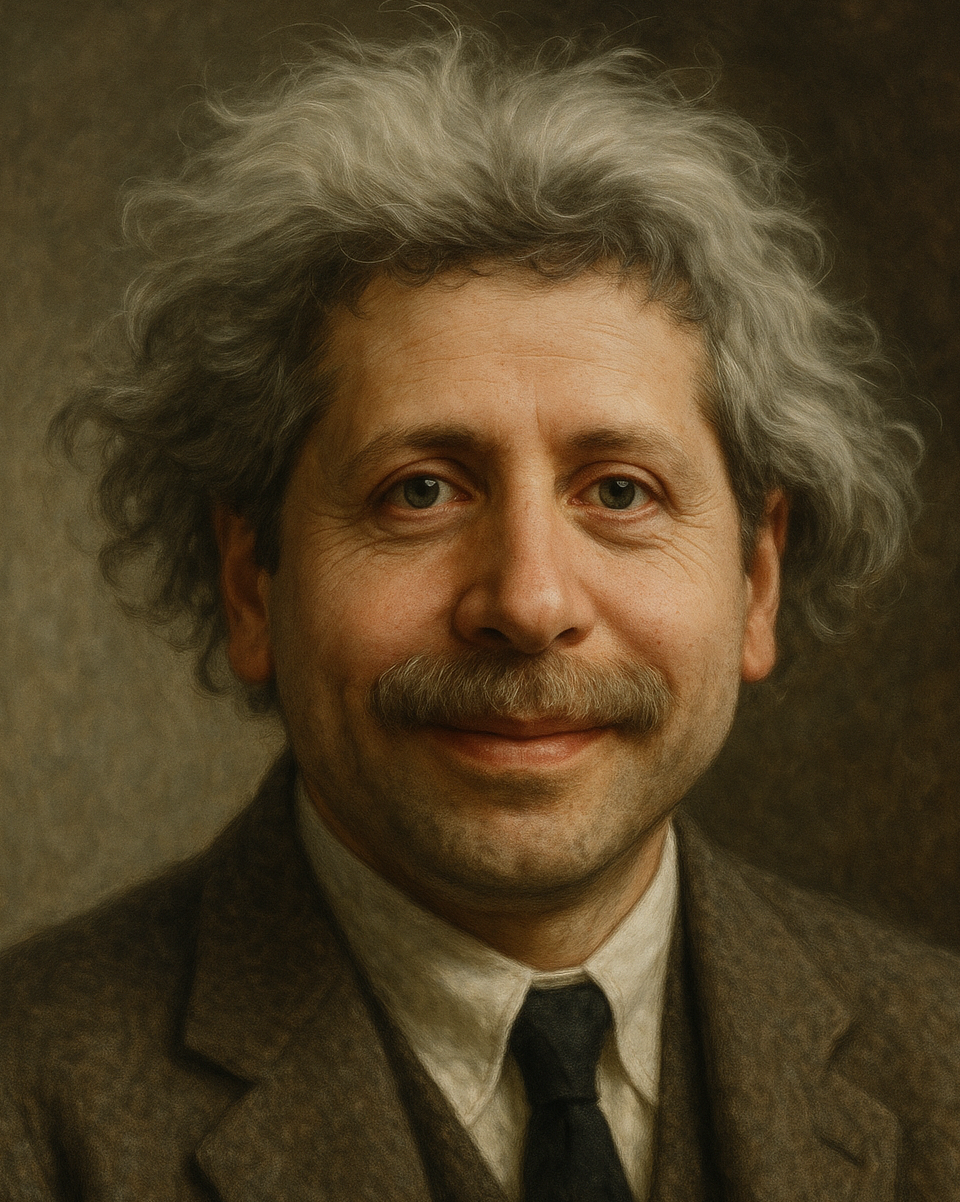

Onchain Oracles: The Impact of AI on Cutting-Edge Research with Steve Hsu

Steve Hsu, theoretical physicist and AI startup founder, discusses his groundbreaking paper where GPT-5 proposed novel theoretical physics equations - the first published physics paper where the main idea came from an AI. Steve explains the generator-verifier pipeline architecture that dramatically improves AI output quality, and why most people have never seen the true capabilities of frontier models.

Audio

Transcript

Contents

Introductions

[00:03] Victor Wong: Okay everyone, welcome to this very special episode of Onchain Oracles. We are going to not cover crypto today, but cover something that I think is very interesting. Our special guest today is Steve Hsu. He is a theoretical physicist and founder of several startups primarily on AI and genomics.

[00:26] Steve Hsu: How are you guys? Great to see you.

[00:29] Victor Wong: We are very happy. Also, I want your help to correct the record because in our year review episode I mentioned one of the exciting developments was really in AI. I mentioned that your paper that got published that you talked about getting AI assistance, but I made a mistake and I think I said it was co-authored by AI, but we'd like to have, you know, that clarity on what actually happened. And of course with us we have our usual host, Bob Summerwill, Head of Ecosystem.

[01:02] Bob Summerwill: And we've got some blurry Kieren and Jim.

[01:05] Kieren James-Lubin: Yes, even closer.

[01:07] Victor Wong: Yes.

[01:08] Kieren James-Lubin: Confused with the backlit. We are in the same location but in separate rooms and so neither setup is completely optimal. But we're here.

[01:17] Bob Summerwill: Maybe don't blur at all.

[01:19] Steve Hsu: Yeah, maybe don't blur.

[01:21] Kieren James-Lubin: Do we know how to turn it off?

[01:22] Steve Hsu: Or put the office potted plant background in?

[01:26] Victor Wong: Yes, exactly, exactly. So why don't we dive right into it? Steve, can you talk about, can you give us a summary of the papers and how AI was used in the creation of papers?

The AI-generated physics paper

[01:37] Steve Hsu: So for listeners who didn't follow all this, and there's sort of different smatterings of this whether you watched what happened on X or on various people's Substacks or on YouTube. So I've been working for the last, most of a year now in evaluating essentially all the frontier models and how good they are at theoretical physics and to a lesser extent pure math.

And on my own podcast, Manifold, there are some episodes about this. There's even an episode with one of the teams that was able to get International Math Olympiad gold performance, gold level performance from off the shelf models. So I've been quite interested in this question of how useful are the models for frontier level work or superhuman intelligence level work in math and physics?

And so I've been working on that in testing the models. I would often, one of the problems with dealing with them, as you guys know, is that they hallucinate. And so it's best to test them in a domain that you really know well, that you know in a super deep level. Otherwise they'll say things very confidently that might just be totally untrue and it might slip past you.

So one of the ways that I test the models is, you know, having been a researcher now for many years and having published, gosh, I don't know, the number might be approaching 150 research articles. I often will ask them, I'll upload one of my old papers and I'll ask the model about it. I'll ask the model to explain it to me. I'll ask the model about other directions in which the research could be continued, in which maybe I and my collaborators thought about it, but we didn't actually publish some of those results.

So there are ways to test its deep understanding, but there are also even ways to test it on things that clearly are not in the literature, that it cannot have memorized from some training source, etc. So it's a very fruitful way to test the models.

And in one case I was testing its understanding of a paper I wrote about 10 years ago, which I actually based on the interactions we had with multiple referees at the time, ultimately the paper was published, but we had lots of interactions with referees along the way. I could tell the community didn't really understand this topic very well. And so I was quite interested to see how well the models could understand it.

I was testing GPT-5. It understood the paper extremely well. And actually it made a suggestion for a continuation of the research which I found super interesting. I had never seen that before, what it proposed. And so then I started investigating its proposal. Now its proposal came in the form of a very long answer which included derivation of a bunch of new equations which I had never seen before. And I then further, I used GPT-5, but then other models as well to then investigate that line of research which turned out to be completely novel and quite interesting. And I wrote a paper based on those results.

[04:50] Victor Wong: Okay, and do you like, I know you wrote a companion piece to that paper also how you used AI through the entire process, was that always your intention to?

[05:01] Steve Hsu: Yeah, well, I should also say that during this period of time I've been working with a team at DeepMind and that team built a specialized AI called Co-Scientist. And Co-Scientist is meant to be a kind of research assistant or research collaborator for scientists.

And I had been doing a lot of testing, trying similar types of things with Co-Scientist. It just happened that this particular novel idea came from during my testing of GPT-5. And so I think GPT-5, of all the models involved deserves the most credit. But I had been doing this kind of thing with the Co-Scientist team.

Now as I was developing the research, I always intended to publish it if it turned out to be good. If it turned out this set of equations was correct and did something useful and was worth thinking about. So I was always thinking, oh, if true, this would be the first example of the model actually suggesting out of the blue, completely de novo, some new idea in theoretical physics which actually really did happen. And I thought that by itself would be remarkable.

So I was thinking about doing that and I was actually talking with the DeepMind Co-Scientist team about this because we were talking about stuff that Co-Scientist was doing for us. But I also mentioned to them very early on I said look what I got from GPT-5. This is like super interesting and maybe this will turn into like the ultimate goal of the Co-Scientist work would also have been to produce a publishable novel result which we would then publish.

Okay, so that was the general thing that we were attempting to do. It just happened to originate in this case from GPT-5. So I was planning to do that.

Now what's the way you can show the community that it's non-trivial? Because I don't want it to rely on my subjective judgment. The way to do that is to get the paper refereed and published in a reasonable journal, in this case a good journal, Physics Letters B.

Peer review and scientific community reaction

Now if you submit the paper and you say, hey, this whole paper is written by AI or the ideas in this paper all came from AI, it's not going to be reviewed in the standard way because people could react emotionally or they don't like AI or they'll just assume it's AI slop, or maybe they'll be the other way and they like AI so they'll treat it in a more favorable way. For whatever reason, I wanted to avoid that.

So when I submitted the paper I filled out the AI declaration. There's now a required AI declaration for most scientific journals. And I said, yes, I use these models in the preparation of this paper. But you're not required to declare something like oh, the original idea for this, the whole paper came from an AI. That's not something you're required to declare. So I did not declare that because I didn't want to bias the process.

Okay. So I believe I got a completely unbiased evaluation of the paper from the referee and the editor at the journal. I don't know who the referee was. I do know who the editor was. Editor's a very well known string theorist in the UK. So I think I got a fair review. I think the paper fully deserves to be published and has novel results.

I have since interacted very strongly with two other theoretical physicists who evaluated the paper and commented on it online. One is a guy at IIT, a professor at IIT, and another is a guy called Jonathan Oppenheim, who's a professor at University College London, who, the second guy I've known for, I don't know, 15, 20 years. 15 years now.

So if you're interested at all in the physics, well, both AI and the physics, but the three of us have done a YouTube podcast discussion together which is almost 90 minutes long and we discuss all this stuff and I think we're pretty close in our opinions now after all of this discussion, you know, and I think we all agree it is worth publishing. There are interesting results, novel results. It's not AI slop.

We might differ on some very fine tuned evaluations of certain aspects of the results and of the paper, but generally we agree.

And so whatever you read online, whatever junk you read online about this paper, I would say forget about that and go watch the 90 minutes or read the transcript of the 90 minutes of our discussion that's just sitting there on YouTube. Otherwise you have no basis for opinion.

Okay. These are the three most qualified people in the world to judge this because they spent the time reading the paper and we've exchanged lots of tons of email and then spent 90 minutes discussing it so that's the place to go for an evaluation of the quality of the work.

[09:41] Victor Wong: It sounds like, in effect, you almost created like a Turing test for scientific validity of an AI-generated idea.

[09:52] Steve Hsu: Well, aside from all the, okay, so some people, I think actually both Nirmalya Kajuri and Jonathan were predisposed to calling it AI slop. Like if you look at the first things they wrote on their Substack, they were pretty negative. And so we had to have back and forths about all this stuff to clarify things.

There's a, I was surprised by this actually, that there's a significant chunk of the scientific community, even the physics, theoretical physics community, which I thought would have been pretty rational about this, that were predisposed toward negativity, toward viewing this as AI slop. So I didn't actually think I was taking any reputational risk because I just thought, oh, I'm going to go through this, I am going through this in good faith with the DeepMind team.

[10:35] Victor Wong: Right?

[10:35] Steve Hsu: And I'm doing this in good faith. And then we, I've discussed this with the DeepMind team. I said, you know, when we get something that's really good, we want to submit it to a journal, but we want to submit it without declaring that it is sort of 100% the work of an AI. We want to just get it refereed and evaluated the way like an ordinary paper of mine. That was sort of our goal.

And then we always agreed we would, at the moment the paper's accepted and we posted on the archive we would acknowledge the exact role of AI in producing paper, which I did. So there's a companion paper to my main paper which actually has literally the prompts and responses from the model. And so there's no hiding anything about the process that produced paper.

But it's best to show that at the end. Like if you show that at the beginning there's enough anti-AI bias that it would distort the process.

[11:31] Victor Wong: I'm curious like, given that reaction and I've seen that because even when I misspoke about what you had done with the paper, that got leveraged to be ammunition against the paper. Even though that was not your mistake in any way that, you know, like in the scientific community does, do you think that makes it much harder to evaluate the benefits or weaknesses of AI in cutting edge research like you're doing?

[12:01] Steve Hsu: I think it does. I, well, I experienced that myself firsthand because I just feel like there was an initial wash of negative, by negative bias. There was initial negative bias that I was just actually not expecting. Maybe it's because I also do research in AI and I'm involved in AI startups. So maybe I just assume people had this naturally kind of open attitude toward, you know, we're doing evals of AIs all the time, so we want to know how good are these things?

Like initially, just one year ago when I was testing the models, their understanding of deeper physics and advanced math was pretty weak. And so the only way you can know that the labs are actually accomplishing their goal of improving is just constant testing and eventually you need expert testing. Right. So I viewed all of this as just a part of that natural participation in the AI research process, the frontier AI evaluation. And I was surprised that there's a subset of the physics community that just saying, oh, this is going to be slop, this is slop, this is terrible, etc. So, yeah, very strange.

Now I think that what this shows though is that there, this is in a way a historic first example. So this is the first published theoretical physics paper in which the main idea came from an AI. I think that's just flatly true.

Unless there's some secret paper other people have published, they just haven't revealed that this is true of. But given my careful sort of monitoring of the model progress in the last year, it's unlikely that that happened much before when it happened for me, because I was doing this very, you know, I was very engaged in doing this kind of thing.

So this might be the first paper in which an AI, it had some idea. It's not like Einstein's theory paper on special relativity, it's nothing like that. But it did connect to previously unconnected areas of physics and make some observation and derive some unique equations.

I should mention that there's a paper in this subject by two authors at Johns Hopkins University, Kaplan and Rajendran. Neither of them were involved in this, although they were involved in some of the correspondence between the three of us later on.

But they have written pretty big papers in the last few years on exactly this topic. And the new equations proposed by the model, by the AI GPT-5, show that their work violates relativistic covariance. So there is a non-trivial outcome that affects the active research of some leading theoretical physicists who were not involved in this at all, who don't use AI at all, as far as I know, or didn't use AI in their work.

So the point is, said something non-trivial which the referees of their papers had not noticed. Okay. And I think Jonathan and Nirmalya Kajuri both acknowledge this. They agree that what the model calculated about the KR work, Kaplan Rajendran work was correct and showed that the Kaplan Rajendran work has some issues.

Right, right. So there's clearly non-trivial stuff happening here. It's just too bad that the way the general Internet world perceives this is through some kind of like AI good AI bad kind of lens.

[15:22] Victor Wong: Oh, sorry, go ahead.

Generator-verifier pipeline architecture

[15:23] Kieren James-Lubin: Yeah, so I had the experience of just using the models kind of casually sometimes for like marketing copy and you know, it's varied on that. Sometimes quite good, sometimes not, and then generating code snippets or just like asking questions.

And I remember very clearly I had the experience of the AI being able to write new code but not able to ingest an existing code base and it switched to oh, it can actually read our code base much faster than any human. And I can answer questions that I had about the code base that I never got a human answer for, maybe because I never asked or, you know, it's remarkably coherent in its understanding. It felt very overnight.

But also there's a skill element and I'm guessing in part, you know, you work with the models for a long period of time, you kind of learn how to get the best output out of them. It's sort of like writing Google searches or SQL queries or something. It's like you got to interact with it a certain way to get the output you want. And I think you covered some of that in your paper. Do you want to tell everybody?

[16:33] Steve Hsu: Yeah, that's a great point, Kieren. This is a very important aspect of the discussion that we haven't touched on yet, but it's very central to the main point. I think that would be useful to most listeners, which is that I didn't just use any process to get these results.

Okay? So when I mentioned the researcher, he's a UCLA CS professor that I interviewed who his team had gotten gold medal IMO performance from off the shelf models, they didn't just do it by making single shot one shot queries of the models, they built a whole pipeline which their terminology, and my terminology is the generator verifier architecture where you chain together or even chain parallel streams of instances of the model or one of many models which are trying to solve the problem and proposing a solution, but then other instances that are critically evaluating what has been previously produced, finding problems with it, making suggestions and then you iterate.

And that process, in the case of the brand new most recent IMO problems, produced 5 out of 6 correct proofs, whereas one shot attempts with any of the top models at the time on IMO problems only got maybe one out of six proofs.

So you can see there's in a sense almost an order of magnitude improvement of the performance if you're willing to expend 10x or more tokens and also chain together differently prompted instances of the model or even different models, which I did in my generator verifier chain I was using multiple different models. I was using GPT-5, I was using Gemini, I was using Qwen.

That is a process which very few people have actually experienced. It's different from, oh, I put it into deep think mode or I use the most recent Claude, but I'm always doing one shot. Okay, I might do a lot of reasoning, but I'm just doing one shot.

Well, try chaining that together many times and don't look at any of the output till the end. And at the end you might find, oh, I have a perfect proof of problem 4 on the most recent IMO. Whereas the one shot thing that was produced is just junk, right?

So anybody who says AI stuff is slop, I have to ask them, well, what are you talking about? Are you talking about the one shot product is slop or are you talking about something that at the end of a pipeline like I just described is slop? Because those are two very different statements.

And the set of people that are able to make a qualified statement about the second thing need to be one, an area expert in some very deep area. And number two, have actually built that architecture and used it. So it's almost a subset, it's almost a measure of like almost zero.

Now, Co-Scientist does do this. Co-Scientist is built to have this kind of chain of generator verifier type things in it. My own process has it, the UCLA thing, which is actually on GitHub. So if you want to prove some IMO, if you want to solve some platinum or IMO problems, you can go download like their GitHub repository and work.

But the point is it's a very small set of people that have seen the maximum level of model capability. Most people have not seen the maximum level of current model capability.

[20:05] Bob Summerwill: And it can be quite time consuming to build those pipelines and they can be quite slow as well. It is quite a difference from here's hardly any context, just magically give me the answer.

[20:18] Steve Hsu: Yeah, so in the case where you have the pipeline built and you don't look in, then it's a very different experience because you don't experience the bad one shot results. You put something in and then of course it may take a lot more time than you're used to, but then if you just look at that output, you'll think that you're dealing with a significantly smarter intelligence than otherwise.

[20:41] Jim Hormuzdiar: You know, I just want to point out this is why the singularity is near, because you can spin up a team of adversarial collaborators with a button press.

[20:50] Steve Hsu: Yeah, no, it's so, so that's my point. So in the companion paper that I wrote to my physics paper, this was the point I was making, is that you should use a generator verifier pipeline. You can get qualitatively better results. And it's a legitimate question, like given the base models that people have produced, what's the right way to get the best outcome? Is there a way to chain them together in a way that enhances the outcome qualitatively? And I would claim the answer is yes.

[21:17] Victor Wong: Do you have any sense of why this works and which different LLMs should be combined in a different way or is it just simply getting one to check another?

[21:30] Jim Hormuzdiar: Isn't it just that like, if you have a room of people arguing, right?

[21:34] Kieren James-Lubin: Like if one is like way dumber than the other, it might throw a bunch of bad critiques in or something. It's interesting. Yeah, it's a good point.

Different models, different capabilities

[21:42] Steve Hsu: Let me give you the empirical, let me, I'll give you the empirical results and then I'll give you some theoretical hypotheses.

So the empirical results are, the UCLA team in the IMO context started with Gemini and then by chaining together the generator verifier instances, they were able to get Gemini to solve five out of six problems.

They subsequently wrote a follow up to their paper or an amendment to their original paper in which they showed they also had gotten the latest GPT and Grok and I forgot one more. At least one more. So they've gotten multiple commercial off the shelf models by using this process. So just instances differently prompted of the same commercial model, but chained together, they had gotten all of those pipelines to the 5 out of 6 level. The 6th problem on the IMO was strangely hard compared to the other 5. Currently the best performance anybody's gotten is 5 out of 6 on these things. So that's an empirical result.

My empirical result is I was testing the models first in one shot mode. And I had concluded at the time, this is a few months out of date now, but maybe six months ago the best models for theoretical physics for me, for what I was asking about were GPT-5, Gemini and Qwen Max. Those were the three best.

And DeepSeek just a little bit behind was DeepSeek and then maybe behind was Grok. So there's variation in how good the models are at that time. You know, that snapshot, there was some variation in the quality of the models. Okay, so that's the empirical result.

Now there's some hypothetical, some hypotheses I could propose. One is that, imagine that you have models that have an X percent chance of detecting an error. Okay, so maybe they have a 60% chance of detecting an error in the previous output that it's looking at, it's critically examining. Well, if you chain together enough like you might, you know, you might have an increased chance of eventually catching all or almost all the errors in what's flowing through the pipeline.

Okay, so I think that's a not unreasonable model for what's happening. So as long as the model instances that you're sticking in there have a reasonable chance of detecting any particular error in a proof or in a physics argument. Like okay, it could be that it's adding value, maybe at some point it's not, you know, it's not able to fully beat down the level of errors to zero, but it's improving the result quite a bit. I think that's a reasonable hypothesis.

Now one thing that I noticed in dealing with lots of models and doing one shot stuff with lots of different models is they fail in different ways. They make different mistakes. All these models have been trained differently. Different pre-training, different RL, different reasoning stuff. Reasoning step like ways of causing it to do reasoning or structuring its reasoning.

So they all fail different ways and so by chaining together very independent instances where one's Qwen and one's DeepSeek and one's, you know, I feel like you have sort of not completely correlated things in there, each of which have an independent chance of catching every error. So you're sort of getting a robust error suppression pipeline going. That's how I view what all this is.

[25:05] Jim Hormuzdiar: I liked Kieren's comment before though. And now I'm going to make a prediction. We are going to see groupthink and bubbles within these collaborators in the future. I'm not saying it's a bad strategy, but I'll bet you that we will see that.

[25:18] Kieren James-Lubin: Maybe less if you mix the models it sounds like.

[25:20] Steve Hsu: But yeah, I mean if you mix the models the models are very different like the Chinese models they have, you know, if you imagine this education system for 1.4 billion people in which they do a lot of testing, they have huge numbers of solved problem sets, solved problems in the Chinese educational system through college and grad school that aren't necessarily in the corpus that say Anthropic or OpenAI are using to train their model.

So there is some genuine independence in the detailed capabilities of the models. You don't see this so much in benchmarks because a benchmark is just one, just giant average score.

But imagine you meet like a grad student came from Bulgaria and he had done all these Soviet era problems and then you meet another grad student who went to UCLA. Well those two guys are going to have different gaps in their knowledge, right? So it's the same, it's the same kind of thing.

[26:14] Kieren James-Lubin: Do you ever see error blow up like, like Jim was saying, like they could theoretically reinforce an error versus?

[26:23] Steve Hsu: I don't, but you can have, so one of the things I comment on in my companion paper is that there were, so the fact that all the models converge doesn't mean that the answer is correct, but it means that there's a, there's a, you know, higher chance that it's correct. Right. Than if they hadn't converged.

When they fail to converge, which is, one model says, no, this is how it goes. And the other model says, wait, that's wrong for this reason. And then you show it to another model and if they just oscillate, I'm pretty like, in my experience, that's a pretty good signal that something's wrong. That just generally like the models are not really understanding this well or calculating right about this. So that did happen in some crucial aspects of the research. And so there I had to really drill down myself and try to figure out what was really going on.

[27:11] Jim Hormuzdiar: But you have seen even within academic humans, bubbles form too.

[27:17] Steve Hsu: So, yeah. Well, do you mean bubbles or cycles where people just don't? Bubbles?

[27:21] Jim Hormuzdiar: I don't know if I want to put you on the record, but there are certain topics in physics which I think you have stated.

[27:25] Steve Hsu: Oh, I see what you're saying. Okay. So you could have a case where everybody agrees and they're all wrong. Yeah. Yeah. So and they're all magnets. Yeah, that can happen with, I'm sure that can happen with the models. And it happens.

[27:37] Jim Hormuzdiar: A is like, kill the humans. And B is like, okay, kill the humans. Hey, yeah, kill the humans.

[27:43] Steve Hsu: Well, remember, you're prompting the verifier instance to be extreme. It's predisposed to be extremely critical of every, that's important. Yeah.

Again, like, for people who only have one shot experience with models, they're dealing with a one shot instance that has been RL'd to be a friendly AI. The AI never says like you're an effing idiot, you know, and all so.

But the thing is like, you can create instances by proper prompting of models that are much more critical and much more predisposed to saying something's wrong. Right. And so by chaining that together, you get something.

[28:25] Jim Hormuzdiar: It is more the referee and a researcher dynamic.

[28:29] Victor Wong: So.

[28:31] Victor Wong: I've experienced this by telling the model like, hey, when you look at this output from another model that it was made by a junior developer or there are obvious mistakes in it. What are they? And that seems to be a better.

[28:44] Steve Hsu: Yeah, you can totally give the verifier instance in the pipeline the prior that there are errors. Right. So, you know, I mean, again, this is not directed at you guys. But for you people out there who are like, AI slop, AI slop. Yes, I'm sure you have seen AI slop, but have you seen the best thing that a determined person can get out of these models? You may not have.

[29:12] Victor Wong: So it makes sense that there is a, well, I think you highlighted two things that are kind of crucially important is that to, that there is a skill in doing this right, even if you follow this process, but also that you need to be a bit skeptical about the output and you need to kind of look at that output kind of probabilistically. Even if it's gone through this process, you gotta say, oh, wait, like, is this, actually I want to verify it before I just assume it's correct?

[29:39] Steve Hsu: Yeah, absolutely, Victor. I mean, I'm only saying that the models are useful to experienced researchers. I make a very specific warning in the companion paper. I say even a PhD, like a senior PhD student or recent PhD, if relying too much on models could produce lots of wrong, subtly, I say in the paper, subtly wrong results because that person doesn't have this huge depth of experience and could be fooled by the model outputs.

The positive statement I'm making is that if you take an experienced researcher, that person's productivity can be enhanced using models the way I describe. So that's a very minimal statement. It's not like, oh, models have replaced physicists or whatever. It just definitely appears to be useful.

Now, both Jonathan and Nirmalya Kajuri, if you listen to our discussion, both agree with me that they find the models useful in their research. And I think a lot of the naysayers don't, without listening to that conversation, would not accept that. They would just think, oh, this, even some other physicists who haven't really experimented much with the models would say things like, oh, it's just going to waste your time. It's all crap. They don't really understand physics. But nobody, I think, who is seriously using the models and trying to do research has that opinion anymore.

Practical applications and future directions

[30:54] Victor Wong: I'm curious on two things. One is, like, how much Steve said.

[31:01] Kieren James-Lubin: He had a hard stop. Oh, yeah, yeah, I can be late.

[31:04] Steve Hsu: I can be a little late for them. So, like, maybe we got four more minutes or five more minutes.

[31:08] Kieren James-Lubin: Four more minutes. Okay.

[31:11] Victor Wong: You know, like, how much time, you know, given that you are like the first person to do this, I'm sure using the models was more cumbersome than a normal person, but do you, what do you think the time savings was by using this model that you experienced or the inefficiency, was it a 2x factor, 10x factor? You know, how do you think about that?

[31:32] Steve Hsu: The proposal of that set of equations I probably never would have done myself. Okay, so that was just a weird leap. Now again, it's not a leap like Einstein jumping to special relativity but it was a non-trivial delta leap that I probably wouldn't have made on my own just because it wasn't, it combined some stuff that I had not really thought that much about myself. But put that aside, that's kind of a one off thing. And just like ask the further refinements, calculations I did for the paper, typesetting the equations in TeX, all that stuff. It definitely saved me weeks of work. There's no question it saved me, you know, definitely like a 2x, at least a 2x speed up in how long it took to complete the paper and.

[32:17] Victor Wong: Oh, sorry. Go ahead Kieren.

[32:19] Kieren James-Lubin: I wanted to get this one.

[32:20] Victor Wong: Okay, last question.

[32:21] Kieren James-Lubin: Day to day use like let's say maybe even not in your formal research capacity like we were talking today. I've never booked a flight with an AI agent. I've had a, Jim has had a route plan. I've kind of route plan, had it plan itineraries. Do you have any tips for more, you know, I don't know, physics layman use cases or just things in your life that we might not have figured out how to do with AI?

[32:47] Steve Hsu: Yeah, so another great question, Kieren. So if you think about what I'm saying with this like generator verifier pipeline, blah blah blah, that's just a very special constrained instance of an agentic pipeline, right? Because like I have two types of agents, generator, you know, really you have generator verifier and then modifier verifier. Right. So you have basically a small set of types of agents in there and they're all sort of doing stuff, pushing stuff through, right?

And you could say like oh, could I have an agentic pipeline that books airplane flights with me? And one of them just knows that like I always want an aisle seat and it's just demanding all the time, like does a reservation and the other one's like Kieren hates flying on Spirit Airlines. Don't ever book.

You know, you could chain together some agents and then like profitably have the thing book reasonable airline reservations free maybe. I haven't tried it. I know there are a ton of companies trying this right now.

You know, generating a proof for a mathematical hypothesis or coming up with correct physics, that's a very constrained problem and the models all kind of agree with each other on what's quote right or wrong. So it's a more constrained problem than like buy me the best fleece puffy jacket from Amazon. Right.

That's like, so I'm not saying that we can solve all those problems right now with agents like the big question of how well agentic pipelines, whether it's encoding or purchasing stuff on the Internet, the rate at which those improve over the next year or two is a very open question and actually plays a big role in whether the AI bubble is going to generate real value for billions of people sooner rather than later. I don't have an answer for that.

But for the very specific thing of like is it useful for professional mathematician or physicist to use this? I would say the answer is definitely yes.

[34:41] Jim Hormuzdiar: But by the way, I just want to put on the record here, it might sound like we're being like devil's advocate a bit here, but I know everybody in this call and 100% of them are super open users of AI for everything right now. Maybe, maybe not everything but for work related tasks. So we're all very pro.

[35:01] Kieren James-Lubin: We'll figure out how to better instrument the verifier pipeline. I do it some. I also do it in just like repeat threads. I try to like tell the AI it's wrong and then you know, see how it comes and sometimes it agrees with me. You know, it's just like a long discussion thread is like a human verifier AI generator. But yeah, I feel I'm still, there's a lot there that we could if we were just better at it. That would be one of the things.

[35:27] Steve Hsu: I'm working on is a, I mean the next phase of this work, this project is to build a pipeline like the kind I've described but for general usage of the whole physics community and eventually, you know, chemistry or math or whoever wants it and in which that all that stuff is hidden.

And yeah, you're maybe burning through lots of tokens and it's expensive. But on the other hand the data that you get back from the way the researcher interacts with this super AI is valuable to the lab.

So I'm actually trying to get that built. So I think you're going to see things like this where the token budget is large and there are many quote agents or generators and verifiers in there working together, and I think that'll be like in the hands of researchers in the next year or two for sure.

Closing

[36:16] Victor Wong: That's incredible. So, on that, I think we'll wrap up. I know you have another appointment to attend to, but thank you so much for your time, as always. Where can people go to if they want to hear more of your thinking on this AI on?

[36:31] Steve Hsu: You know, if you're not already tired of, if you're not already tired of me, go on X and you'll see a lot more of me. My X feed. And I have a podcast called Manifold that every two weeks, I release an episode. Usually I'm interviewing somebody else.

[36:46] Victor Wong: Awesome. And we'll make sure to include links of this in our notes. Thanks again, Steve. Take care.

[36:50] Steve Hsu: All right, guys, make crypto great again.